During the past five years there has been accumulating in the files of the United States Air Force, Royal Canadian Air Force, Department of Transport, and various other agencies, an impressive number of reports on sightings of unidentified flying objects popularly known as "Flying Saucers". These files contain reports by creditable people on things which they have seen in the sky, tracked by radar, or photographed. They are reports made in good faith by normal, honest people, and there is little if any reason to doubt their veracity. Many sightings undoubtedly are due to unusual views of common objects or phenomenae, and are quite normal, but there are many sightings which cannot be explained so easily.

Project Magnet was authorized in December, 1950, by Commander C.P. Edwards, then Deputy Minister of Transport for Air Services, for the purpose of making as detailed a study of saucer phenomenae as could be made within the framework of existing establishments. The Broadcast and Measurements Section of the Telecommunications Division were given the directive to go ahead with this work with whatever assistance could be obtained informally from outside sources such as Defense Research Board and National Research Council.

It is perfectly natural in the human thinking mechanism to try and fit observations into an established pattern. It is only when observations stubbornly refuse to be so fitted that we become disturbed. When this happens we may, and usually do, take one of three courses. First, we may deny completely the validity of the observations, or second, we may pass the whole subject off as something of no consequence, or third, we may accept the discrepancies as real and go to work on them. In the matter of Saucer Sightings all three of these reactions have been strikingly apparent. The first two approaches are obviously negative and from which a definite conclusion can never be reached. It is the third approach, acceptance of the data and subsequent research that is dealt with in this report.

The basic data with which we have to work consist largely of sightings reported as they are observed throughout Canada in a purely random manner. Many of the reports are from the extensive field organization of the Department of Transport whose job is to watch the sky and whose observers are trained in precisely this sort of observation. Also, there are in operation a number of instrumental arrangements such as the ionospheric observatories from which useful data have been obtained. However, we must not expect too much from these field stations because of the very sporadic nature of the sightings. As the analysis progresses and we know more about what to look for we may be able to obtain and make much better use of field data. Up to the present we have been prevented from using conventional laboratory methods owing to the complete lack of any sort of specimens with which to experiment, and our prospects of obtaining any in the immediate future are not very good. Consequently, a large part of the analysis in these early stages will have to be based on deductive reasoning, at least until we are able to work out a procedure more in line with conventional experimental methods.

The starting point of the investigation is essentially the interview with an observer. A questionnaire form and an instructional guide for the interrogator were worked out by the Project Second Storey Committee, which is a Committee sponsored by the Defense Research Board to collect, catalogue and correlate data on sightings of unidentified flying objects. This questionnaire and guide are included as Appendix I, and are intended to get the maximum useful information from the observer and present it in a manner which it can be used to advantage. This form has been used so far as possible in connection with the sightings investigated by the Department of Transport.

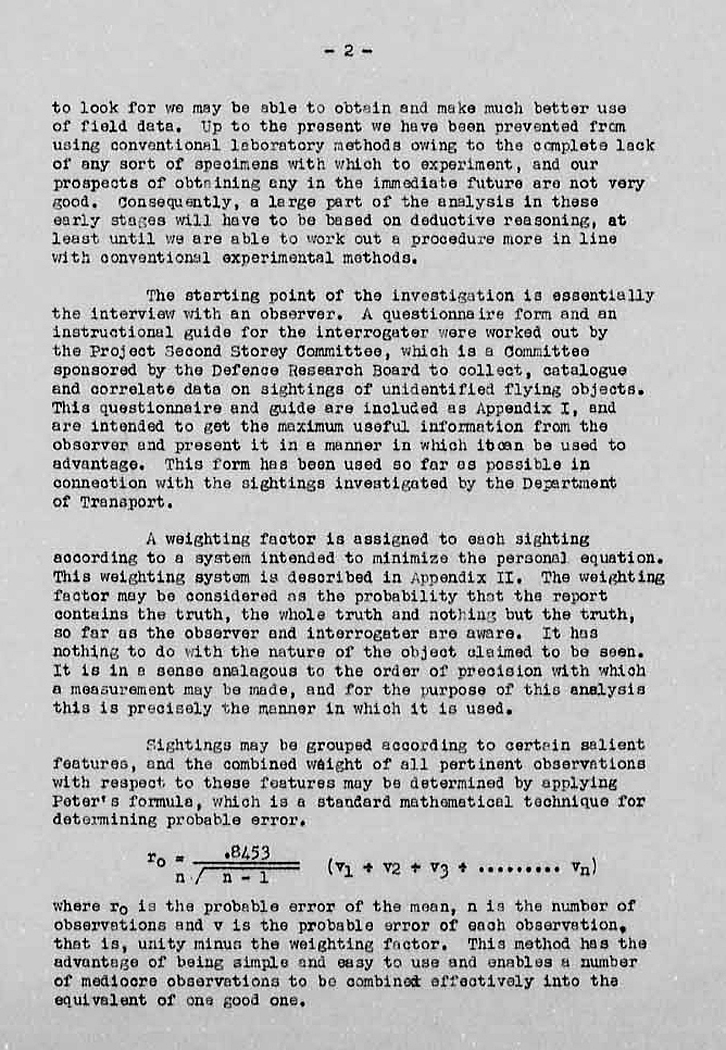

A weighting factor is assigned to each sighting according to a system intended to minimize the personal equation. This weighting system is described in Appendix II. The weighting factor may be considered as the probability that the report contains the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so far as the observer and interrogator are aware. It has nothing to do with the nature of the object claimed to be seen. It is in a sense analagous to the order of precision with which a measurement may be made, and for the purpose of this analysis this is precisely the manner is which it is used.

Sightings may be grouped according to certain salient features, and the combined weight of all pertinent observations with respect to these features may be determined by applying Peter's formula, which is a standard mathematical technique for determining probable error.

| .8453 | ||

| ro = |

|

(v1 + v2 + v3 + .......... vn) |

| n √ n - 1 |

where ro is the probable error of the mean, "n" is the number of observations and "v" is the probable error of each observation, that is, unity minus the weighting factor. This method has the advantage of being simple and easy to use and enables a number of mediocre observations to be combined effectively into the equivalent of one good one.

The next step is to sort out the observations according to some pattern. The particular pattern is not important as the fact that it should take account of all contingencies however improbable they may appear at first sight. In other words, there must be a compartment somewhere in the scheme of things into which each sighting may be placed, comfortably, and with nothing left over. Furthermore, it must be possible to arrive at each appropriate compartment by a sequence of logical reasoning taking account of all the facts presented. If this can be done, then the probability for the real existence of the contents of any compartment will be the single or combined weighting factor pertinent to that single or group of sightings. The charts shown in Appendix III were evolved as a means for sorting out the various sightings and provide the pattern which was used in the analysis of those sightings reported to and analyzed by the Department of Transport.

Most sightings fit readily into one of the classifications shown, which are of two general types; those about which we know something and those about which we know very little. When the sightings can be classified as something we know about, we need not concern ourselves too much with them, but when they fit into classifications which we don't understand we are back to our original position of whether to deny the evidence, dismiss it as of no consequence, or to accept it and go to work on it. The process of sorting out observations according to these charts and fitting them into compartments can hardly be considered an end in itself. Rather, it is a convenience to clarify thinking and direct activity along profitable channels. It shows at once which aspects are of significance and which may be bypassed. Merely placing a sighting under a certain heading does not explain it; it only indicates where we may start looking for an explanation.

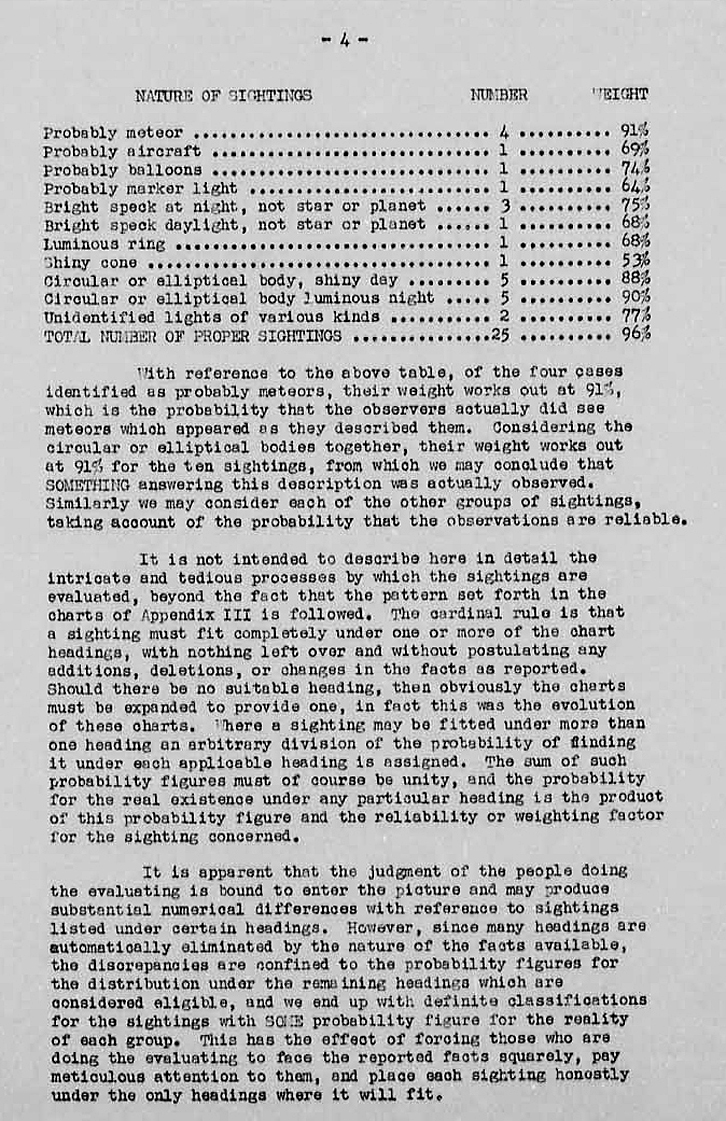

Appendix IV contains summaries of the 1952 sightings as investigated by the Department of Transport. Considerably more data exists in the files of other agencies, and more is being collected as the investigations proceed. While it is not intended to make any reference to an analysis of the records of other agencies, it may be said that the Department of Transport sightings are quite representative of the sightings reported throughout the world. The following is a table of the breakdown of the 25 proper sightings reported during 1952.

| NATURE OF SIGHTING | NUMBER | WEIGHT |

|---|---|---|

| Probably meteor | 4 | 91% |

| Probably aircraft | 1 | 69% |

| Probably balloons | 1 | 74% |

| Probably marker light | 1 | 64% |

| Bright speck at night, not star or planet | 3 | 75% |

| Bright speck daylight, not star or planet | 1 | 68% |

| Luminous ring | 1 | 68% |

| Shiny cone | 1 | 53% |

| Circular or elliptical body, shiny day | 5 | 88% |

| Circular or elliptical body luminous night | 5 | 90% |

| Unidentified lights of various kinds | 2 | 77% |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF PROPER SIGHTINGS | 25 | 96% |

With reference to the above table, of the four cases identified as probably meteors, their weight works out at 91%, which is the probability that the observers actually did see meteors which appeared as they described them. Considering the circular or elliptical bodies together, their weight works out at 91 % for the ten sightings, from which we may conclude that SOMETHING answering this description was actually observed. Similarly we may consider each of the other groups of sightings, taking account of the probability that the observations are reliable.

It is not intended to describe here in detail the intricate and tedious processes by which the sightings are evaluated, beyond the fact that the pattern set forth in the charts in Appendix III is followed. The cardinal rule is that a sighting must fit completely under one or more of the chart headings, with nothing left over and without postulating any additions, deletions, or changes in the facts reported. Should there be no suitable heading, then obviously the charts must be expanded to provide one, in fact this was the evolution of these charts. Where a sighting may be fitted under more than one heading an arbitrary division of the probability of finding it under each applicable heading is assigned. The sum of such probability figures must of course be unity, and the probability for the real existence under any particular heading is the product of this probability figure and the reliability or weighting factor for the sighting concerned.

It is apparent that the judgment of the people doing the evaluating is bound to enter the picture and may produce substantial numerical differences with reference to sightings listed under certain headings. However, since many headings are automatically eliminated by the nature of the facts available, the discrepancies are confined to the probability figures for the distribution under the remaining headings which are considered eligible, and we end up with definite classifications for the sightings with SOME probability figure for the reality of each group. This has the effect of forcing those who are doing the evaluating to face the reported facts squarely, pay meticulous attention to them, and place each sighting honestly under the only heading where it will fit.

In working through the analysis of the proper sightings listed, we find the majority of them appear to be of some material body. Of these, seven are classed as probably normal objects, and eleven are classed as strange objects. Of the remainder, four have a substantial probability of being material, strange, objects, with three having a substantial probability of being immaterial, electrical, phenomena. Of the eleven strange objects the probability definitely favours the alien vehicle class, with the secret missile included with a much lower probability.

The next step is to follow this line of reasoning as far as possible so as to deduce what we can from the observed data. Vehicles or missiles can be of only two general kinds, terrestrial and extra-terrestrial, and in either case the analysis enquires into the source and technology. If the vehicles originate outside the iron curtain we may assume that the matter is in good hands, but if they originate inside the iron curtain it could be a matter of grave concern to us.

In the matter of technology, the points of interest are: - the energy source; means of support, propulsion and manipulation; structure; and biology. So far as energy is concerned we know about mechanical energy and chemical energy, and a little about energy of fission, and we can appreciate the possibility of direct conversion of mass to energy. Beyond this we have no knowledge, and unless we are prepared to postulate a completely unknown source of energy of which we do not know even the rudiments, we must conclude that the vehicles use one of the four listed sources. Unless something we do not understand can be done with gravitation, mechanical energy has little use beyond driving model aircraft. We use chemical energy to quite an extent, but we realize its limitations, so if the energy demands of the vehicles exceed what we consider to be the reasonable capabilities of chemical fuels, we are forced to the conclusion that such vehicles must get their energy from either fission or mass conversion.

With reference to the means for support, propulsion and manipulation, unless we are prepared to postulate something quite beyond our knowledge, there are only two groups of possibilities, namely the known means and the speculative means. Of the known means there is only physical support through the use of buoyancy or airfoils, the reaction of rockets and jets, and centrifugal force, which is what holds the moon in position. Of the speculative means we know only of the possibility of gravity waves, field interaction and radiation pressure. If the observed behaviour of the vehicles is such as to be beyond the limitations which we know appy to the known means of support, then we are forced to the conclusion that one of the speculative means must have been developed to do the job.

From a study of the sighting reports (Appendix IV), it can be deduced that the vehicles have the following significant characteristics. They are a hundred feet or more in diameter; they can travel at speeds of several thousand miles per hour; they can reach altitudes well above those which would support conventional aircraft or balloons; and ample power and force seem to be available for all required maneuvers. Taking these factors into account, it is difficult to reconcile this performance with the capabilities of our technology, and unless the technology of some terrestrial nation is much more advanced than is generally known, we are forced to the conclusion that the vehicles are probably extra-terrestrial, in spite of our prejudices to the contrary.

It has been suggested that the sightings might be due to some sore of optical phenomenon which gives the appearances of the objects being reported, and this aspect was thoroughly investigated. Charts are shown in Appendix III showing the various optical considerations. Enticing as this theory is, there are some serious objections to its actual application, in the form of some rather definite and quite immutable optical laws. These are geometrical laws dealing with optics generally and which we have never yet found cause to doubt, plus the wide discrepancies in the order of magnitude of the light values which must be involved in any sightings so far studied. Furthermore, introducing an optical system might explain an image in terms of an object, but the object still requires explaining. A particular effort was made to find an optical explanation for the sightings listed in this report, but in no case could one be worked out. It was not possible to find os much as a partial optical explanation for even one sighting. Consequently, it was felt that optical theories generally should not be taken too seriously until such time as at least one sighting can be satisfactorily explained in such a manner.

It appears then, that we are faced with a substantial possibility of the real existence of extra-terrestrial vehicles, regardless of whether or not they fit into our scheme of things. Such vehicles of necessity must use a technology considerably in advance of what we have. It is therefore submitted that the next step in this investigation should be a substantial effort towards the acquisition of a much as possible of this technology, which would no doubt be of great value to us.