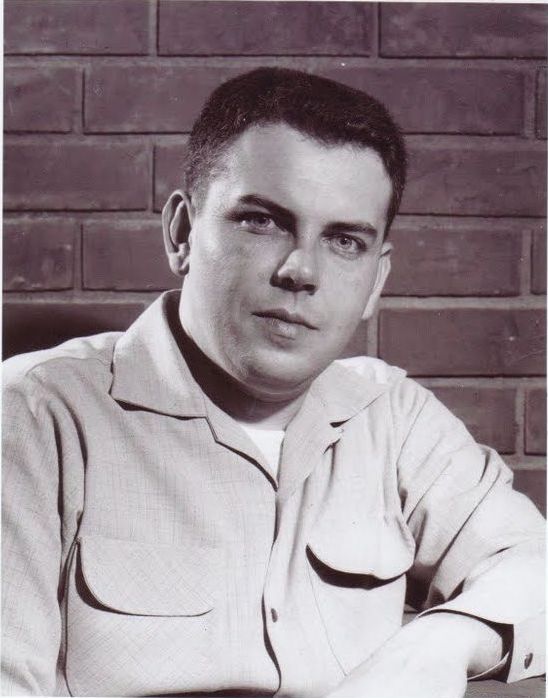

Edward J. Ruppelt : True, The Man's Magazine,

: True, The Man's Magazine,

: True, The Man's Magazine,

: True, The Man's Magazine, Un récit de True

Le 12 août 1953, une femme du Corps des Observateurs au Sol

dans les Black Hills du Dakota du Sud signala une lumière en survol dans le ciel à l'est de sa position. 2 opérateurs

d'une station radar sortirent pour vérifier s'ils voyaient la chose alors que la femme était encore au téléphone.

Alors qu'ils scrutaient le ciel, la femme rapporta, la chose commence à se déplacer au-dessus de Rapid City.

Au

^même moment, les 2 hommes du radar observèrent la lumière commencer à bouger. Ils revinrent à leur radar pour la

réperer et la femme rapporta que l'objet revenait à sa position d'origine. Le radar le repéra à ce moment.

Un F-84, en vol à ce moment-là, fut dirigé vers la cible. Le pilote du jet observa la lumière visuellement et commença à la suivre. L'objet se dirigeait vers le nord avec le jet à ses trousses, et les opérateurs du radar observaient la chasse sur leur écran. L'Objet Volant Non Identifié restait devant le jet et semblait gagner de vitesse à chaque fois que le pilote accélérait. Après avoir pris en chasse l'objet sur 120 miles, le pilot manqua de carburant et fut autorisé à rentrer. Lorsque le jet vira de bord l'ovni vira aussi et le suivit.

Après que le jet ai atterri, un 2nd F-84 partit investiguer. He was talked into position and spotted the thing visually above him. He went up to 20,000 feet, reported that he was level with the light and again the object took off to the north with the jet in pursuit. Again the chase was observed on ground radar, with both the UFO and the jet showing plainly on the scope.

In the second pursuit, the pilot made a number of tests to rule out some of the common phenomena that have been mistaken for "flying saucers." He turned off all his instrument lights and kicked the plane around to make certain that he was not chasing a canopy reflection. He was not. He observed the object carefully in relation to the stars, and swore that it moved across them, thus eliminating the possibility that he was chasing a planet or a star. Finally, when he thought he was closing in on the object, he switched on his radar gun sights. This type of jet has a light on the instrument panel that goes on to indicate a "lock on" with the target by the radar sights. The light went on.

The second jet chased the light 160 miles to the north before abandoning the pursuit. This time the UFO continued flying north. The Ground Observer Corps Filter Center ahead was alerted and observers there reported a light speeding north.

This was indeed an astounding occurrence. There were simultaneous visual sightings from two ground sites linked by telephone, simultaneous ground and radar sightings, simultaneous ground-radar and jet-visual sightings, a pursuit in which the UFO outran the jet, a reversal in course, a second jet-visual sighting confirmed by ground radar, an air-radar "lock on" and finally a sighting from the ground hundreds of miles away.

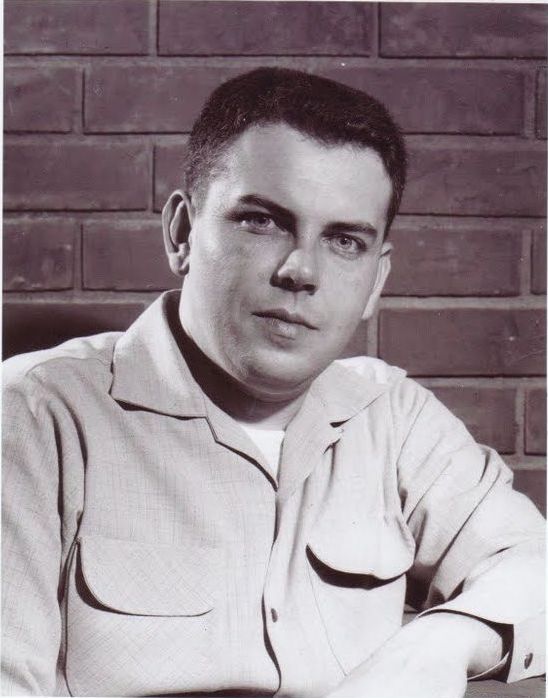

What was the object? For two years, from 1951 to 1953, I flew 200,000 miles, conferred with dozens of top American scientists and an exotic collection of hot-eyed screwballs, stumbled through Florida mangrove swamps, dragged myself out of bed at 3 a.m. to answer transatlantic telephone calls, inspected scores of strange photographs and watched one short amateur movie ninety-seven times in an effort to answer this and similar questions.

My colleagues and I were lambasted by fellow Americans for concealing the biggest news story in the history of modern man, and by Radio Moscow for the setting the stage for atomic war. I was called an ignorant dupe, a Charlie McCarthy manipulated by powerful forces in the Pentagon. I was consulted by the White House, and I briefed the highest figure in the Air Force, who listened respectfully and let me do all the talking.

For two years, with the help of the best brains in the country, we worked on a giant jigsaw of a puzzle that was either utterly meaningless or would rock the world.

For every piece that we fitted into place, we found that two more had been added to the puzzle pile.

I finally found myself soberly inspecting a piece of cow manure to learn if it had come from outer space.

From 1951 to 1953, I was in charge of the official Air Force investigation of Unidentified Flying Objects, the things that whiz through space under the popular name of "flying saucers."

The Age of the Flying Saucer was in Year Five when it plucked me out of my job as technical intelligence analyst for the Air Technical Intelligence Center at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio.

Year One had opened on June 24, 1947, when a Boise businessman named Kenneth E. Arnold reported seeing a chain of nine "

reported seeing a chain of nine "saucerlike things

" glinting in the sun

as they flew at 1,200 mph – twice the speed of sound – near Mt. Rainier. His story snared the nation's imagination

with one baffling fact. No known aircraft in the world had broken the sound barrier at that time. "I don't believe

it,

" Arnold said, "but I saw it.

"

If Arnold's story had stood alone, the Age of the Flying Saucer would have opened and closed with a one-day stand.

But in the next thirty days there were fifty-three more reports of saucers. Near Portland, Oregon, a couple of deputy

sheriffs reported "twenty in a line going like hell to the west.

" A Chicago housewife saw one "with legs

"

and ran into the house and slammed the door. A prospector in the Cascade Mountains spotted five or six of them "with

tails

" and was startled to see his magnetic compass "gyrating wildly

." In Spokane, a woman reported five

of them "about the size of a five-room house.

" Hers were shaped "like washtubs

." A remarkably cool

gentleman in Seattle spoke out and reported, "Why, they come through our yard all the time.

"

At the time, I was out in Yellowstone National Park, on vacation from Iowa State College, where I was studying aeronautical engineering. It was my second try for a degree. I had dropped out the first time, in 1942, to enlist in the Air Force. I had been assigned as bombardier in the first B-29 squadron organized, flown the Hump out of India, and then moved over to Tinian for the big raids against Japan. Our group flew the last mission of the war, a raid against Tokuyama, just 15 minutes before the end of the war.

Within a few days after Arnold's sighting,

youngsters were tossing paper plates over our lodge at Yellowstone and yelling, "Saucer, saucer!

" Some of the

tourists started seeing things and would come in and tell about them, as if their vacation was complete. I read

Arnold's story and shrugged it off. Twice over Japan I'd seen strange objects in the sky. One was an orange-yellow

light that followed our B-29 for awhile and then suddenly winked out. The consensus was that it was a "foo fighter" – the strange light spotted

dozens of times over Europe and Japan. The theory was that it was a static-electricity phenomenon. Another time,

flying home with jumpy nerves after a rough mission, I cut loose with six .50-caliber guns at a bright object just

about dawn. After getting the crew in an uproar, I suddenly realized I was shooting at the planet Venus.

Among the sightings that followed Arnold's, however, there appeared some that looked like more than hysteria. They

came from pilots acquainted with the tricks that flying can play on the eyes, from scientists, from other presumably

sober and unexcited observers. A meteorologist in charge of the U.S. weather bureau station at Louisville, Ky.,

reported an orange light "rolling through the night sky.

" At Muroc Air Field, in California, site of secret

government experimental plane tests, Lt. Joseph McHenry spotted "two silver objects of either spherical or disklike

shape.

" He summoned three other people from the base and they saw the same things. Three more witnesses joined

the group, and five of the seven saw a third object. No experimental craft were in the air. The objects moved against

the wind and hence were not balloons. A few hours later, a major and a colonel at Muroc made a separate sighting of "a

thin metallic object" that sported over the field for eight minutes.

Two United Air Lines pilots, Emil J. Smith and Ralph Stevens, flying from Boise to

Portland, reported following four or five "somethings" for 45 minutes before they "disappeared in a burst of speed."

They described them as "

and Ralph Stevens, flying from Boise to

Portland, reported following four or five "somethings" for 45 minutes before they "disappeared in a burst of speed."

They described them as "thin and smooth on the bottom and rough appearing on the top.

"

The Air Force, I learned later, wavered between two schools of thought during this first rash of sightings. Some fairly high officials felt concern over them. The U.S. had seen complacency lead to one Pearl Harbor, and international tensions were beginning to tighten under the climate of the "cold war." These officials felt that we ought to find out – and quickly – what was causing the epidemic of saucer stories.

Opposed were those who argued that Arnold's story had triggered a mass hysteria. They felt that the publicity given to the first sightings set millions of people to scanning the sky to "see a saucer," and that they deluded themselves with all sorts of things – blowing paper, birds, reflections from planes. This group reasoned that the sightings would dwindle in the normal course of events.

The skeptics were bolstered by the discovery that Arnold's account had some holes in it. His estimates of the size of the objects and their distance from his plane did not jibe. He reported them to be 20 to 25 miles away and from 45 to 50 feet in length. When his sighting was analyzed, it was discovered that objects of that size cannot be resolved by the naked eye at that distance. If his estimate of size was correct, the objects were only six or seven miles away – and flying at about 400 mph, well inside the range of conventional craft.

The early skepticism was strengthened when none of the objects indicated any menace, landed, or crashed where examination would establish that they were indeed something new under the sun.

The early dispute over the handling of the Unidentified Flying Objects stories was settled by the UFO's themselves. They persisted, month after month, with a hard core of incidents that came from seasoned observers and defied analysis. The Air Force decided to concentrate the investigation and build up a body of data that could be analyzed.

They set up Project Sign and went after the saucers in earnest. Later the code name was switched to "Grudge." We changed it later to "Blue Book" when someone in the Pentagon suggested that "Grudge" gave the impression that the project was tackling the job begrudgingly. The code "Blue Book" was taken from the traditional college blue books which had all the answers to the examination questions. It did not prove a particularly apt choice.

The sightings kept coming in through 1947, 1948, 1949 on an average of about one every three days. The controversy over them built up and the confusion multiplied. Articles began to crop up in international magazines and radio commentators periodically broadcast "the inside story of the saucers," with each account contradicting the other. They were secret U.S. weapons, new Russian craft, emissaries from another planet scouting the earth.

In , the Air Force submitted the 375 sightings then on hand to an intensive reevaluation and issued

a thick report on its findings. Dr.

The Rand Corporation commented: "We have found nothing which would seriously controvert simple rational

explanations of the various phenomena in terms of balloons, conventional aircraft, planets, meteors, bits of paper,

optical illusions, practical jokers, psychopathological reporters and the like.

"

Dr. Hynek: Assuming evidences of observers and investigators to be correct, it is concluded that 32 percent can be

explained astronomically, 35 percent can be attributed to birds, balloons, sky rockets, aircraft, etc., and 38 percent

either lacked necessary evidence or a suitable explanation was not apparent.

The USAF Air Weather Service stuck to its own field, commented that "12 percent apparently were balloons.

"

Of the 375 reports, 13 percent did not have readily explainable solutions. Dr. Fitts advanced a theory: "There are

sufficient psychological explanations for the reports of Unidentified Flying Objects to provide plausible explanations

for reports not otherwise explainable. These errors in identifying real stimuli result chiefly from the inability to

estimate speed, distance, and size.

"

Supporting these analyses were bulky articles of carefully reasoned and qualified considerations of the data. The press, always eager for an answer that will fit into two lines of headline type that counts twelve letters to the a line, condensed the whole report into a "write-off" by the Air Force. The UFOs ignored the Rand Corp., Dr. Hynek, the press, et al, and continued to fly. In 1950 exactly the same number landed in the project files – 152 – as showed up in 1949.

Then in 1951, they began to dwindle.

Meanwhile I had finished my college work at Ames and had rolled up my new sheepskin just in time to be recalled to Air Force duty because of Korea. They stationed me at Dayton, where for the first seven months I worked on conventional aircraft that you can see, feel and measure.

The primary function of the Air Technical Intelligence Center is not, as some people believe, analyzing the UFO mystery. It is charged with the prevention of technological surprise by a foreign country. It studies all the data it can get on enemy aircraft, guided missiles, and technological advances on anything that flies. It got the saucer project because the one thing that every observer agreed on was – the things flew.

This once stirred a harassed Blue Book investigator to complain. "Why in the hell don't the damn things swim so we can turn them over to the Navy?"

By the summer of 1951, Grudge was down to one man, the sightings were dwindling, and it looked as if the project would fold for lack of business. In June, for the first month in four years, not a single sighting came in. In August the lone investigator was transferred, and the project was turned over to a friend of mine, Lt. Jerry Cummings. I used to drop in and kid him about the poor state of the saucer business.

"You're going to be out of work, boy,

" I told him.

"You're right,

" he told me, "but for the wrong reason. I got a discharge coming up.

"

At 3 p.m. Sept. 12, 1951, the project suddenly came to life. The ATIC teletype began chattering out a yard-long message from northern New Jersey. When it signed off, it looked as if the Garden State had been invaded by something out of Herbert George Wells.

It had started two days before, on Sept. 10, at 11:10 a.m., when a student operator was giving a demonstration to a group of visiting brass at a radar school in New Jersey. He had been picked for the show because he was the top man in his class. He demonstrated the set under manual operations for awhile, picking up local air traffic. Then he announced that he would demonstrate automatic tracking, in which the set is put on a target and follows it without help from the operator. The set could track objects flying at jet speeds.

The operator spotted an object about 12,000 yards southeast of the station, flying low toward the north. He tried to lock on for automatic. He failed, tried again, failed again. He turned to the audience of VIP's embarrassed.

"It's going too fast for the set,

" he said. "That means it's going faster than a jet.

"

A lot of very important eyebrows lifted. What flies faster than a jet?

The object was in range for three minutes and the operator kept trying without success, to get an automatic track. It finally went off the scope, leaving a red-faced operator talking to himself.

Twenty-five minutes later, the pilot of a jet trainer, carrying an Air Force major as passenger and flying 20,000 feet over Point Pleasant, N.J., spotted a dull silver disklike object far below him. He described it as 30 to 50 feet in diameter and as descending toward Sandy Hook from an altitude of a mile or so. He banked over and started down after it. As he shot down, he reported the object stopped its descent, hovered, then sped south, made a 120-degree turn and vanished out to sea.

The Jersey puzzle then switched back to the radar group. At 3:15 p.m. they got an excited call from headquarters to pick up a target high and to the north – which was where the first "faster than a jet" object had vanished – and to pick it up in a hurry. They got a fix on it and reported that it was traveling slowly at 93,000 feet. They also could see it visually as a silver speck.

What flies 18 miles above the earth?

The next morning two radar sets picked up another moving target that couldn't be tracked automatically. It would climb, level off, climb again, go into a dive. When it climbed, it went almost straight up.

The two-day sensation ended that afternoon when an unidentified hovering object was picked up for several minutes.

A copy of the long New Jersey report went to Washington, and shortly later Dayton got instructions to go up, investigate and report to the Pentagon. In a matter of hours, Lt. Cummings and an ATIC lieutenant colonel were flying out to see what was up.

Two days later they were back with reams of raw data. Before Cummings could start sorting out the jigsaw, he got his discharge.

Up to this point, I had done the work I was assigned to and paid little attention to flying saucers. But the New Jersey outbreak fascinated me. Whatever had happened there was plainly a lot more than the occasional "saucer" story I'd read in the papers, where a Dakota farmer saw something zip over his barn, or a housewife saw six disks wobbling through the sky while she hung up her wash. My curiosity overcame the ancient rule that men in uniform have followed since Hannibal's day. I volunteered.

I told myself that I'd solve the Jersey puzzle and then go back to my regular work. It turned out that I did neither. As if to jeer at my brash confidence, the UFOs suddenly started flying all over the country. In a matter of days I found myself down in Texas tangled up in one of the classics of the saucer saga – the Lubbock lights.

I went into the UFO investigation with curiosity and no preconceptions. I soon found that the job had enormous difficulties. The basic one was that there were no precedents, rules or manuals for chasing flying saucers. The evidence you work with – with few exceptions – is the recollection of observers, usually excited, puzzled or frightened humans trying to describe events completely foreign to their experience. And what they had seen usually appeared unexpectedly and vanished in a matter of seconds. After a few months I got so I could predict the start of their stories.

"Now listen,

" they would say, in a mixture of apology and belligerence, "I never believed in those things

before. I laughed at them like everybody else. You can check me with any of my friends. I'm not cracked and I wasn't

drunk. I don't know what it was, but I tell you, I SAW it....

"

What did they see? Trying to evaluate it led you into a dozen complex technical fields – psychology, meteorology, physiology, astronomy, aerodynamics, electronics, physics, logic, chemistry, plain and fancy detective work.

Most of the people we talked to tried earnestly to tell us exactly what they had seen. But human beings are imperfect observers. This is not something unique to saucer sighters. Police and newspapermen have struggled with it for years. Ten eyewitnesses to an auto wreck will tell ten different stories, and each will be positive that his is the true account. Autos travel only 60 or 70 miles an hour. The incidents we investigated involved things supposedly moving as fast as 25,000 miles an hour. And they were seen from great distances, usually under the worst possible conditions for accurate reporting, often at night and for only a few seconds.

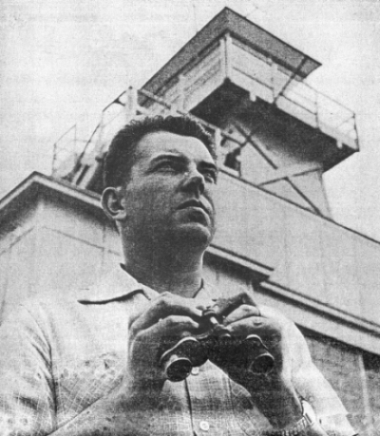

The data in the Lubbock case was much better than in 99 percent of the incidents that came into Blue Book. It involved multiple sightings by a group of Ph.D.'s, backstopped by a series of independent sightings. In addition, there were pictures – four of them.

The sightings had been going on for weeks before we got word of them. They had started on the evening of August 25, when four professors from Texas Technological College were sitting in the back yard of one of their homes watching for meteors. At 9:30, a flight of weird bluish-green lights, in a roughly crescent formation, raced across the sky. The sight caught them by surprise. Being men of science, the deplored the fact that their first startled observation had been hasty and incomplete. The vowed to do better if the lights reappeared. That night they made a second sighting. In the next few weeks, they made twelve more.

When I got to Lubbock, they had compiled what data they could. They had measured the angular velocity and found it to be 30 degrees per second. In an effort to compute the speed, they had set up an ingenious two-way radio system and had tried to get sightings from two spots and make a rough triangulation. This had failed but the failure provided a clue.

The sightings had been reported to the local paper. In the nights following the first appearance of the flying lights they were seen by hundreds of nonprofessional witnesses. Arguments were raging all over Lubbock as to whether the objects were secret missiles, space ships – or ducks.

On the night of August 31, an 18-year-old amateur photographer shot some pictures. He had the prints and the negatives. The pictures were later reproduced all over the world, and are included in almost every book about the saucers.

"I was lying in bed when I saw a flight of the lights go over,

" he said. "I grabbed my loaded Kodak 35 and

went out in the back yard. In a little while a second flight came over and I made two shots. Then a third flight

passed over and I took three more shots.

" The camera was set at f/3.5 and the shutter at 1⁄10 of a second.

His prints were clear, and showed the lights in a sharply defined V. One of the negatives had been misplaced, but we had four for analysis. Each showed 18 lights in the V formation, with a larger one off to the right. This was promptly labeled "the mother ship" by the science-fiction boys – an analysis that struck me as about 99 percent fiction and about one percent science.

Close examination showed a peculiarity in the pictures that has been ignored in almost every account of them that I have read. There is a marked dissimilarity in the lights in the four pictures. In one, they are diagonal dashes; in the next, roughly circular; in the third they are tadpole-shaped, with their tails all pointed to the left; in the fourth, they are like arrowheads. In each picture, the "mother ship" changes shape to match her brood.

I have read dozens of accounts that "the Air Force indicated these pictures to be authentic.

" The Air Force

said nothing of the sort. The pictures were submitted to intense scrutiny at the photo laboratory at Wright Field.

There was little that could be evaluated. There were no points of reference in the pictures – only the lights. The

photo had not been retouched. The Air Force said only that "The photos were never proved to be a hoax.

"

The endless retellings of the Lubbock story recount the multiple sightings, the impeccable reputation of the observers, the supporting evidence of the "authentic" pictures – and stop there. The full story contains some intriguing facts. It is told here for the first time.

First, whatever the pictures show, they are not the lights seen by the professors. They looked at the pictures and said so. Their first two sightings were roughly crescent, the rest showed no geometric pattern – V-shaped or otherwise. None of the independent sightings was V-shaped either. The pictures, however, are as precise in formation as a double row of Radio City Rockettes.

Second, the pictures were taken on a clear night, with plenty of stars. No stars show in the pictures. This means that the lights were much brighter than the stars – and in Texas, the stars at night are big and bright. Neither the professors nor the other observers described their lights as big and bright. Theirs were dull and glowing.

Third, with much of the town scanning the sky, no one else in Lubbock reported the lights on August 30, when the photographer saw his three bright, spectacularly geometric flights. Fourth, we reconstructed the scene later at Dayton, attempted to duplicate the pictures, and failed. The photographer had showed me the site in his backyard. Because of trees and other obstructions, it afforded a span of 120 degrees of clear sky. I questioned him about the speed at which the lights crossed the sky. He estimated it at 30 degrees a second – a figure that agreed with the earlier estimates by the professors. To double check, I had him move his hand across the sky and checked him. It was close to 30 degrees a second. This gave him four seconds in which to shoot each flight – two pictures one time, three the next.

The Kodak 35 has a hand wind to feed fresh film into place. At Dayton we simulated 120 degrees of open sky with lights traveling 30 degrees a second, took a Kodak 35, and tried to shoot and wind until we had three shots. We couldn't do it. We tried over and over with different people. The best anyone could squeeze in was two badly hurried shots. And with the shutter at 1/10th of a second the two shots were badly blurred.

In poking around Lubbock, I talked to many people who had seen the lights and were sure that they were birds. One old gentleman had seen the lights several nights. His description matched that of the professors.

"Shucks, officer,

" he drawled. "Them things is plovers.

"

I went off to read up on plovers. They're water birds about the size of quail with light breasts that could reflect light. A local game warden told me there were plovers in the vicinity.

A few blocks from the area where most of the sightings had been made was a boulevard lighted by mercury vapor lights that gave off an intense bluish-white glare. Then I recalled an odd bit of information. When the professors had tried to set up a second observation post elsewhere, they saw nothing, while the sightings continued at the original spot – near the lighted boulevard.

Four times in the following year, at Fargo, N.D., Greenville, S.C., Randolph Air Force Base, and Bakersfield, Calif., we got cases that duplicated the Lubbock affair. Each time they proved to be birds reflecting ground lights.

The project files carry the Lubbock lights as "unknown." The pictures were never proved to be a hoax. Maybe, under intense excitement, one man in a thousand can shoot three unblurred shots with a handheld Kodak 35 in four seconds. I'll believe it when I see it done.

But so far as what the professors saw, I think that 10-gauge shotgun would have brought down the Lubbock saucers in a shower of feathers.

While I was in Lubbock, a temporary investigator, Lt. Henry Metscher, had made some sense out of the Jersey mystery that had lured me into saucer chasing. Among the data that Cummings had brought back on the "faster-than-a-jet" radar objects were some plots on locations and times. It turned out that the objects that had outsped the automatic tracking and startled the VIPs actually plotted out at an unspectacular 400 mph. On questioning, the operator conceded that he had got excited because of the visiting brass. The object undoubtedly was a conventional plane.

The "disk" spotted over Sandy Hook by the jet? Merscher learned that a large balloon painted silver for radar tracking had been launched near Sandy Hook just before the pilot and the AF major saw their UFO. What about the maneuvering? Hang on to that question for a bit.

The excited call the next morning from headquarters? Another balloon carrying a radar target. The HQ officers had a bet on about its altitude, wanted a fast report, didn't bother to tell the radar crew the reason for the urgency. By this time the radar boys had the saucer fever and were ready to see anything. The second supersonic object proved to be a weather blip. The last saucer that hung ominously over New Jersey was definitely tabbed as another balloon.

I congratulated Metscher and settled down to the business of knocking off saucers like an ace skeet shooter. If the saucers can laugh (we had several that whistled), they probably zipped through the stratosphere chuckling to themselves.

One of the many things I did was go back over the files of the project from its inception. There were some odd facts and some baffling sightings. One thing I learned was that Arnold wasn't the Columbus of the flying saucer at all. The project had thirteen listings prior to June 24, 1947 – the supposed dawn of the Saucer Era. They all had come into the project after Arnold told his story, with the usual explanation that the observers had been reluctant to tell their tales until Arnold had broken the ice.

Among the post Arnold sightings were three classics – the tragedy in which Capt. Thomas Mantell was killed, the dogfight between an F-51 and a light at Fargo, N.D., and the sighting of a "space ship with lighted windows" by an airliner near Montgomery, Ala.

The Mantell case was headlined across the nation

as "Flier Killed Chasing Saucer

." His tragedy is interwoven with saucerian folklore, and frequently is told in

conjunction with a local story of a plane that takes off after a "thing" in the sky and is never seen again. I have

heard local variants of this story perhaps twenty times. Each time the account starts out: "You remember when

Mantell was shot down by a saucer? Listen to what happened here last month....

"

On the afternoon of January 7, 1948, two airmen in the control tower at Godman AFB, near Louisville, Ky., began getting calls about an unidentified object spotted by civilians in the area. They checked with Flight Service about experimental craft, were told that none was in the vicinity. Shortly later, one of them spotted an object from the tower, pointed it out to his companion. They summoned their officers, who also saw something.

At this point, four F-51's of the Kentucky National Guard approached the base. Mantell, the flight leader, was asked to check on the object and try to identify it. One of his planes had to land because of fuel shortage. Mantell and the other two took out after the thing in the sky.

The Air Force account of the case was monumentally fouled up. It had all three fliers describing the object as "metallic and of tremendous size," and told how Mantell climbed away from his mates, radioing reports back to the tower until he suddenly fell silent. Some time later his body was found with the wreckage of his plane scattered over a wide area. The account then reports that the first analysis of the case indicated that he was chasing the planet Venus.

The obvious public reaction to this account was: "Who do they think they are kidding?

" If three fliers agreed

that the thing was "metallic

" and "tremendous

" how could it have been the planet Venus? Later in the

project, we had many instances of pilots mistaking Venus (and other planets) for something flying through the sky.

None of them ever described it as "tremendous.

"

In examining the original reports on the tragedy, I learned the following:

ice cream cone tipped with red," a description that was picked up in the Air Force release as agreed upon by all the observers. Actually, the other descriptions varied greatly: "

round and white," "

huge and silver or metallic," "

small white object," "

one-fourth the size of the full moon," "

one-tenth the size of the full moon."

What the hell are we looking for?" When the other landed, he described it as "

resembling a reflection in the canopy."

metallic and of tremendous size."

The project learned later that there was a huge skyhook balloon in the vicinity. It was spotted later southwest of Louisville by two observers with telescopes, and was identified as a balloon. Such identification should have plucked the planet Venus out of the Air Force speculation.

Why should an experienced pilot like Mantell chase a balloon? The skyhooks were new at that time so he may not have known about them. To him a balloon was one of the small weather models frequently launched from air fields.

What happened to his plane? Why was the wreckage scattered over such a wide area if it was not blown to bits by a hostile saucer?

The wreckage showed that the plane was trimmed to climb. Mantell had no oxygen aboard, and he was near 20,000 feet – almost four miles up – when his wingmen abandoned the climb. It is likely that he blacked out from lack of oxygen. At some higher altitude, the plane's power would drop off and the F-51 level out with an unconscious man at the controls. The propeller torque would pull it in to a slow left turn, into a shallow dive, then an increasingly steeper descent under power. Somewhere during the screaming dive, the plane reached excessive speed and began to break up in the air....

Classic No. Two – the "dogfight between the plane and the saucer." It is listed as the lone case of "combat" between a plane and a saucer. Actually there were three other such cases.

The pilot was George F. Gorman, a 25-year-old second lieutenant in the North Dakota Air National Guard. On October 1,

1948, starting at 9 p.m., he chased an apparently disembodied light for 27 minutes in his fast F-51. He described the

UFO as "a small ball of clear white light, between six and eight inches in diameter.

" For awhile it winked on

and off, then it appeared to put on power and glowed steadily. Gorman pushed his F-51 to the limit and was unable to

catch it. He reported that it made one turn that he couldn't follow and twice came at him in what appeared to be

ramming attacks. Both times he dived his plane out of the collision course. The "dogfight" ranged from low level up to

17,000 feet, and the light finally pulled straight up and disappeared.

"I had the distinct impression that its maneuvers were controlled by thought or reason,

" Gorman said.

Four other observers at Fargo partially corroborated the story. An oculist, Dr. A.D. Cannon was near the field in his

plane with a passenger, Einar Neilson. They saw a light "moving fast,

" but did not witness all the maneuvers

that Gorman reported. Two CAA employees on the ground, saw a light move over the field once.

Here are the other dogfight cases:

On June 21, 1952, at 10:58 p.m., a Ground Observer Spotter reported that a slow-moving craft was nearing one of our atomic energy installations. An F-47 patrol in the area was vectored in visually, spotted a light and closed on it. They "fought" from 10,000 to 27,000 feet and several times the object what seemed to be ramming attacks. The light was described as white, 6 to 8 inches in diameter, blinking until it put on power. The pilot could see no silhouette of anything attached to it. The similarity to the Fargo case is striking.

On the night of Dec. 10, 1952, near another atomic installation, the pilot and radar observer of a patrolling F-91 spotted a light while flying at 26,000 feet. They checked and were told that no planes were known to be in the area. They closed on the object and saw a large, round white "thing" with a dim, reddish light coming from two "windows." They lost visual contact, but got a radar lock-on. They reported that when they attempted to close on it again, it would reverse direction and drop away. Several times the plane altered course itself because collision was imminent. There was a solid undercast of clouds, which would eliminate the possibility of refraction of ground lights.

In each of these instances, as well as in the case narrated next, the sources of the stories were trained airmen with excellent reputations. They were sincerely baffled by what they had seen. They had no conceivable motive for falsifying or "dressing up" their reports.

The other "dogfight" occurred September 24, 1952, between a Navy pilot of a TBM and a light over Cuba. It had a sequel that revealed some fascinating information about the illusions the supposedly objective human eye can contrive.

"As it (the light) approached the city from the east it started a left turn. I started to intercept. During the first part of the chase the closest I got to the light was 8 to 10 miles. At this time it appeared to be as large as an SNB and had a greenish tail that looked to be five to six times as long as the light's diameter. The tail was seen several times in the next 10 minutes in periods from 5 to 30 seconds each. As I reached 10,000 feet it appeared to be 15,000 feet and in a left turn. It took 40 degrees of bank to keep the nose of my plane on the light. At this time I estimated the light to be in a 10 to 15 mile orbit.

"At 12,000 feet I stopped climbing, but the light was still climbing faster than I was. I then reversed my turn from left to right and the light also reversed. As I was not gaining distance, I held a steady course south trying to estimate a perpendicular between the light and myself. The light was moving north, so I turned north. As I turned, the light appeared to move west, then south over the base. I again tried to intercept but the light appeared to climb rapidly at a 60 degree angle. It climbed to 35,000 feet, then started a rapid descent.

"Prior to this, while the light was still at approximately 15,000 feet, I deliberately placed it between the moon and myself three times to try to identify a solid body. I, and my two crew men, all had a good view of the light as it passed the moon. We could see no solid body. We considered the fact that it might be an aerologist's balloon, but we did not see a silhouette. Also, we would have rapidly caught up with and passed a balloon.

"During its descent, the light appeared to slow down at about 10,000 feet, at which time I made three runs on it. Two were on a 90 degree collision course, and the light traveled at tremendous speed across my bow. On the third run I was so close that the light blanked out the airfield below me. Suddenly it started a dive and I followed, losing it at 1,500 feet."

When he landed, anyone who would have tried to tell him he was chasing a lighted weather balloon would have had a rough time. Twenty-four hours later, he was convinced that he had chased a balloon.

The following night, a lighted balloon was sent up and the pilot was ordered up to compare his experiences. He duplicated his "dog fight" – illusions and all. The Navy furnished us with a long analysis of the affair, explaining how the pilot had been fooled. It is recommended reading for anyone who believes that an experienced pilot cannot be fooled by what he sees.

In each of the four cases of "dog fights," including Gorman's, a balloon was known to be in the vicinity.

In the case involving the ground observer and the F-47 near the atomic installation, we plotted the winds and calculated that a balloon was right at the spot where the pilot encountered the light.

In the other instance, with the "white object with two windows," we found that a skyhook balloon had been plotted at the exact site of the "battle."

Why can't experienced pilots recognize a balloon when they see one? If they are flying at night, odd things can happen to their vision. There is the problem of vertigo, as well as disorientation brought on by flying without points of reference. Night fighters have told dozens of stories of being fooled by lights.

The third saucer classic did not involve a saucer at all, but a "wingless aircraft, 100 feet long, cigar-shaped and about twice the diameter of a B-29." It was sighted the night of July 24, 1948, near Montgomery, Ala., by C.S. Chiles and J.B. Whitted, pilots of an Eastern Airlines plane. The underside of the thing had a "deep blue glow," there were "two rows of windows from which bright lights were glowing, and it had a 50-foot trail of orange-red flames!" Only one passenger of the flight was awake at the time. He saw only "a trail of fire."

On the basis of later experience, the project was fairly sure that this was meteor. At about the same time, a plane flying between Blackstone, Va., and Greensboro, S.C., reported independently that it had see a "bright shooting star" in the direction of Montgomery.

On the night of November 24, 1951, there was a similar incident, with multiple sightings. It started when a CAA tower in southern Michigan told the Air Force Flight Service that an airline crew had seen a huge object with bluish-white flames going southwest at an extremely high speed. At about the same time, other reports flooded in from Air Force personnel at Selfridge AFB, north of Detroit, from a soldier on leave at Battle Creek, from another CAA tower, from some sheriff's deputies. All reported the same sort of object going the same direction. Most of them described it as rocket-shaped. One, an experienced pilot, was certain it was a V-2 type missile. All these observers – at scattered points – reported the thing "about four miles east." It turned out to be a very large meteor passing over the New England states; we verified it with experienced meteor observers and the time checked to the dot. I talked to a number of the witnesses later and they remained firm in their belief that they had seen a Something.

The science-fiction boys, of course, converted the Chiles-Whitted Something into another "mother ship.

" It was

in sight for only a few seconds, was seen by only three people, and then vanished into the dark night. But it flies on

endlessly in the pages of saucer lore, a transport from outer space packed to the gunwales with flying disks.

It is popular folklore among the more fanatical saucer fans that the Air Force has either bungled or deliberately

sabotaged the saucer investigation. Our sterner critics imply that a saucer could land within ten feet of a Project

Blue Book man, and he would turn his back on it and walk away. Frank Scully says, "It's high time that the Air

Force stop fumbling with the saucer question and turn the investigation over to a competent civilian group.

"

It is utter nonsense, of course, to charge that Blue Book doesn't want to verify the existence of the saucers. If

they come from outer space, the first man to lock down proof of it would go down in history with a bigger name than

Christopher Columbus. He'd be remembered when such minor figures as U.S. Presidents were long forgotten. Every time a

good sighting came into Blue Book, you could feel the suppressed excitement run through the staff, an unspoken "Maybe

this is it.

"

Here is what Blue Book did in its efforts to pin down the facts about the flying saucers. Virtually all the evidence we had to work with was the reports of witnesses. Shortly after I took over the project, we set about preparing a model questionnaire that would get the maximum amount of data from the witnesses. If there was a pattern to the saucer stories, we wanted to find it.

The project had tried a variety of questionnaires in the past. We gathered all these together along with a cross section of accounts by witnesses. We took this material to the psychology department of a Midwest university that is noted for the excellence of its statistical questionnaires. We got together a panel of engineers, physicists, mathematicians, astronomers and psychologists to list the questions they would like to have answered. The project also listed the things it wanted to know. The psychologists determined whether it was feasible to expect an eyewitness to answer each question and if so, how it should be worded.

When we got through with all this, we used the result as a test model, and sent it out to several hundred saucer-sighters. When the reports were returned, we revised the questionnaires again, from the way it had worked out. The result is the standard questionnaire that Blue Book is using today.

The questionnaire ran eight pages and had 68 questions. It was booby-trapped in a couple of places to give us a cross-check on the reliability of the reporter as a witness. We got quite a few questionnaires answered in such a way that it was obvious that the signer was drawing on his imagination.

From the standard questionnaire, the project worked up two more. One dealt with radar sightings of UFOs, the other with sightings made from a plane.

At the instigation of Blue Book, the Air Force sent out orders to every one of its installations in the world, instructing them on the reporting of "saucers." Immediate reports were to be made by wire to ATIC, listing the basic data such as time, date, location, description of the object, names of observers, etc. These initial reports were to be followed up with expanded written reports. Blue Book was also given authority for direct communication with any installation in the U.S., thus cutting a lot of red tape and speeding up the investigations.

This AF regulation, unfortunately, was issued on the same day that Life magazine came out with a flying-saucer story that reversed its previous attitude and considered the question soberly. A lot of people added two and two and got six. The story went around that Life was "softening up the public for the truth" while the new Air Force regulation was "alerting the military." Actually, it was coincidence.

We obtained the cooperation of astronomers all over the country. Scores of them were queried on whether, in their constant watching of the skies through giant telescopes, they had ever seen anything that resembled a space ship. The answer was no. There are also a number of stations across the U.S. where automatic cameras photograph the sky at intervals every night the year around to help track meteors. We asked these people if their cameras had ever caught anything that resembled a flying saucer. The answer was no. Both the astronomers and the sky-photographers were asked to notify the project if they ever turned up anything unusual. They never did.

We sent out special cameras to places where there had been a high number of sightings in an effort to get pictures of our own. Each camera had two lenses, one of which had a diffraction grid to split light into its component parts and thus give a clue to the source of the light – whether it was coming from a jet's tail, a balloon, or what? We had a lot of trouble with the cameras, and got only five or six pictures, all of which were worthless. The light-gathering power of the lenses was too low. The cameras have been re-equipped, and the Air Force recently has redistributed them.

We did not rely solely on our own resources in trying to unravel the UFO riddle. In January 1952, Col. Frank Dunn, then chief of ATIC, decided that we should hire several well-qualified scientists on a consultant basis, to help us gather certain technical information, to review outstanding "unknowns," to go over our conclusions and to suggest future courses of action. The names of these people have never been made public, and it is unlikely that they will be. The project learned early that publication of anyone's name in connection with the saucer stories brought on a deluge of mail, telephone calls and visits from cranks.

The invariable comment of scientists who examined the project's data was that they offered insufficient solid information for evaluation. Several hundred people, of all different sorts, said they had seen something that they couldn't explain, under a wide variety of circumstances. Where did you go from there?

The new questionnaire and the Air Force order came at a fortunate time – just before the enormous upsurge of sightings in 1952. By the end of the year we had a much better collection of data — both in quantity and quality — and we decided to summon a week-long conference of scientists to look it over and tell us what they thought.

They met early in 1953. Like our consultants, they cannot be named, and for the same reasons. But the group consisted of some of the nation's top people in astrophysics, operational research, intelligence, physics and psychology.

First we briefed them thoroughly on the operation of the project, on our methods of evaluation, on our conclusions and how we arrived at them. When were through, they examined the "best" of the UFO cases that the project had been unable to explain. They viewed movies, looked at still photographs of "saucers," and heard reports from specialists on radar and photo-interpretation.

At the end of the week, they unanimously concluded that we had nothing that proved – or even indicated – that any type of vehicle was violating U.S. air space. There was discussion that possibly some new natural phenomenon was causing some sightings, but this was rated doubtful.

On the possibility of emissaries from outer space, they made this statement: "We as a group do not believe it is

impossible for some other celestial body to be inhabited by intelligent creatures. Nor is it impossible that these

creatures could have reached such a state of development that they could visit earth. However, there is nothing in the

so-called "flying saucer" reports that would even vaguely indicate that this taking place.

"

This group viewed – and rejected as proof of the existence of saucers – the controversial Tremonton movies.

These pictures were taken at 11:10 a.m., July 2, 1952, a few miles out of Tremonton, Utah, by Warrant Officer Delbert Newhouse, a Navy photographer. He was driving in his car with his wife when they saw some white objects circling in the blue sky. Newhouse took out his camera, a 16 mm. Bell and Howell, and shot 40 feet of film. After he had the film developed, he sent it to Blue Book for analysis.

I've sat through ninety-seven showings of the film. When I first saw it, I was impressed by it – and puzzled. It shows several groups of white spots orbiting against the blue Utah sky. There are no points of reference – only the moving spots and the sky. Near the end of the film, one of the spots moved away from the others, and Newhouse panned the camera along to follow it. When turned back, he reported, the other spots had vanished.

I sent the film on to the Pentagon, where it was received by Maj. Dewey Fournet, liaison man for ATIC. Fournet, an excellent engineer, holds strongly that saucers are real and come from outer space. He has since left the service and is in private industry in Texas. He was tremendously excited with the movies.

The movies were inspected by a group of high officers at the Pentagon and were sent back to Dayton for analysis by the Air Force photo laboratory. The lab examined them and reported that there was no evidence of fraud, and that the objects were not spherical balloons. It was the consensus of everyone who viewed the movies, incidentally, that they were not a hoax, that they showed something that Newhouse and his wife had seen. We decided to send them on to the Navy photo lab for further evaluation. They were taken there by Fournet, and I understand that he gave them quite a buildup to the Navy technicians.

The Navy subjected them to an intense analysis, involving thousands of man-hours of work, and came up with an astounding report. The gist of their evaluation was that the movie was authentic, and that the objects were not birds, balloons, planes, or anything earthly. They examined the film, frame by frame, and analyzed the density of light on each object. They reported that the objects appeared to be rotating in three groups, with each light increasing in brilliance, then decreasing, disappearing and returning as if spinning about an axis.

On the panel of scientists that inspected them later were some men with excellent reputations in the field of astronomical photo analysis. They viewed the movie a number of times, and questioned the Navy analysts closely about their methods of evaluation. They concluded that the Navy's method of measuring light density had been faulty, and the conclusions drawn from it were therefore unsound. They suggested that the whole study be redone by new methods before the analysis be released.

Among the panel were a number of people who were convinced that the objects were sea gulls soaring on a thermal current. This theory also has been advanced by other persons familiar with gulls, who had seen the movie earlier. The ultimate decision of the experts was that the movie did not warrant the great time and expense of second analysis.

At the time I was doubtful of the gull explanation. But later, while in San Francisco on an investigation, I saw a group of gulls soaring on a bright day over the bay. I was astounded by the similarity between the sight before my eyes and the movie that I had seen almost 100 times.

The project received three other movies that got considerable attention. One, in color, was taken at Great Falls, Mont., and showed two bright spots of light speeding across the sky and passing behind a water tower. Two F-94's were in the area, and the lights could have been reflections of the sun on these jets, but we were not able to come to any definite conclusion.

The other two movies were made at White Sands Proving Grounds with Askania Cine theodolites – scientific tracking cameras for following guided missiles. The first was made on April 27, 1950. Shortly after a missile was fired and had soared into the stratosphere and fallen, someone spotted an object in the sky. The theodolites were hooked up by an intercom system, and several stations were instructed to try to get pictures. Unfortunately, only one camera had film. The pictures showed a smudgy, dark object, not very well defined. It was moving.

On May 29, 1950, after word of the first picture had got around and the stations were more alert, another object was sighted just before a missile was to be fired. A second station was called, and they reported that they also could see the object visually. Both stations swung into action and took photos. On developing the film, it turned out that each was tracking a different object – bright dots of light – and again we had no triangulation. Whatever the dots were, they were impossible to evaluate.

As a result of these incidents, the Air Force set up "Project Twinkle," two Askanias to be manned 24 hours a day. The project was operated for a year and didn't get a picture. It was first set up in an area where there had been many "saucer" sightings, but as soon as it was in operation, the sightings stopped and we began to get a flock of sightings from another area about 100 miles away. After months of inaction, the Askanias were moved to that spot, whereupon the sightings stopped there and resumed at the original site.

When I told this story to a dedicated saucer fan later, he had an immediate explanation. "Of course,

" he said,

"the saucers were watching you guys.

"

We were always on the lookout for "hardware" – any sort of tangible object that conceivably might have dropped, been wrenched or stolen from a saucer. We got a variety of things that people said had fallen from the sky and we had them all analyzed. Among them were some slag from Virginia, an aluminum mop handle from Washington, D.C., and a tar-covered marble from Illinois.

Once a Texan reported that something had flashed across the sky and plunged through the ice into a pond on his farm. Investigators went out with hollow tubes and probed into the ooze under the jagged hole in the ice. They sent me one sample of the cross section from their pipes that puzzled them. It turned out to be cow manure.

We naturally tended to give more credence to sightings from a group of witnesses than from a single observer. One person can have spots before his eyes or hallucinations, but they won't be seen by a friend. This elementary rule-of-thumb resulted in one saucer-sighter risking his happy home in an effort to convince us.

We got a report, from a town that is going to remain nameless, that a citizen was sitting in his car when it was buzzed by a flying saucer. We wrote back to the intelligence officer to whom the report was made and asked him if there was any corroboration, pointing out that an unsupported story was – an unsupported story.

"Look, mister,

" the citizen told the officer, "I'm not the only one who saw it. There was a woman with me,

and she saw it too. The trouble is, she wasn't my wife.

" This was the lone case that we received of a saucer

flying down Lovers' Lane.

Because of a run of saucer incidents that turned out to be balloons, we attempted to set up a system that would give us information on every balloon in the country. The complex project yielded some results, but explained only a small percentage of the unknowns.

We got flying-saucer reports from a weird assortment of origins – an oil drum exploding in a city dump, paper plates

caught in an updraft, bugs silhouetted against the sun. Birds flying over a well-lighted area, like an athletic field

at night, caused a lot of reports of "glowing objects.

"

We were always being collared by volunteer experts. Each non-believer always had some revolutionary theory that would

explain away every saucer in the country. Invariably it was something that fifty people had thought about years

before. For some reason or other, there were a lot of military generals who "knew what the saucers are.

" They

would tell us that each sighting was just a reflection on a plane's canopy, and then go into long stories about their

own experiences with canopy reflections. Whenever we were badly outranked we would listen carefully and try to nod at

the proper time.

About the fifteenth time that an earnest member of the brass started unveiling the canopy reflection theory, I rebelled.

"Look, sir,

" I said, "what about the thousands of sightings on the ground by people who don't have

canopies?

"

"Hmmm," mused the two-star theorist, "I never thought of that."

The variety of the UFOs, the many different circumstances under which they were sighted – in bright sunlight, at dusk, at night, from planes, from the ground, by radar, by groups of people – should have ruled out any attempts to explain them away by a single theory. But people kept trying.

Professor Donald H. Menzel , in a book entitled Flying Saucers – History, Myth,

Facts, attempted a single explanation for the stubborn 20 percent of unknowns that the project could not account

for. His theory was that "this mysterious residue consists of the rags and tags of meteorological optics, mirages,

reflections in mist, refraction and reflections of ice crystals."

, in a book entitled Flying Saucers – History, Myth,

Facts, attempted a single explanation for the stubborn 20 percent of unknowns that the project could not account

for. His theory was that "this mysterious residue consists of the rags and tags of meteorological optics, mirages,

reflections in mist, refraction and reflections of ice crystals."

His explanation failed to account for the many cases where there was a simultaneous radar fix on a UFO and a visual sighting. Mirages and reflections can and do fool the naked eye, but they don't show up simultaneously on a radar scope.

On the one batch of spectacular UFOs that looked as if they ought to have a meteorological explanation, the explanation collapsed. These were the flock of green fireballs that appeared in the Southwest.

They caused considerable concern because they showed up in sizable numbers around the Atomic Energy Commission's vital installations at Los Alamos and Sandia. They all showed the same characteristics and were seen by hundreds of people, including a lot of top-flight government technicians and scientists.

They were large, often described as big as the full moon, only brighter, and kelly-green in color. They traveled at terrific speeds at apparently low altitudes. One airline pilot flying west of Albuquerque swerved his plane, nearly throwing the passengers out of their seats, in his fear that he was going to collide with one. They began appearing in December 1948, and had their biggest night on December 5, when crews of both civilians and military aircraft and ground observers sighted them. They appeared sporadically afterward, and then vanished. I talked to many people who had seen the fire balls, and they have been an impressive sight.

The obvious initial theory was that they were meteors, and that they had shown up in one section of the country by a fluke of the law of probability.

Dr. Lincoln La Paz, director of the Institute of Meteoretics at University of New Mexico, strongly opposed this theory. He is one of the world's leading authorities on meteorites – and he had seen the green fireballs. I had a long talk with him in July 1952, and he had some convincing reasons.

I heard many reports that the copper content of the air in the New Mexico area showed a marked increase during the invasion of the weird green balls of fire. This was reported flatly as fact by a national magazine. We tried diligently, but were unable to authenticate this story.

On the green orbs, the project draw a blank, and the visitors to the Southwest remain a big question mark in the Blue Book files. But whatever the emerald mysteries were, they were a separate puzzle from the classic flying saucers. They had no characteristics in common with the silvery disks except they flew.

As our experience in investigation broadened, we found that the reliability of saucer reports varied inversely with the detail that the observer reported. The hoaxes were almost always marked by a vivid description. When a witness could tell us exactly how many rivets the saucer had, we started checking his background.

One morning when we arrived at work we found an urgent telegram from a Military Air Transport Service base in Florida. It told about a scoutmaster who had been attacked by a saucer and burned. The incident had been witnessed by three scouts, and the local intelligence officer had made a quick check on the story and could find no holes in it. He reported that the scoutmaster had a good reputation for reliability, which of course is what you'd expect.

I showed the report to my superior at ATIC, Col. Frank Dunn, and he approved an on-the-scene investigation. In 20 minutes we had a B-25 ready with two pilots. I threw some things in a bag, got Lt. Robert Olssen, a Blue Book investigator, and we headed for Florida. Just before we left, we called Florida and asked them to have a doctor examine the scoutmaster's burns.

We landed late in the afternoon and reviewed the case with the local intelligence officer. He was pretty well sold on the man's story. It was an exceptionally detailed account, and when I heard the whole thing, I smelled a hoax. He said that he had conducted a scout meeting in the basement of a church, and at the end of the meeting, started to drive four of the boys home. He dropped off one, and then headed into the nearby town where the other three lived. He took a back road that led through a sparsely settled area. This struck me as odd, but I checked the map and found that it was the logical route from the first scout's house to the town where they were going.

By this time, his story went, it was around 9 p.m. As they drove through a sandy section with scrub pine, he saw some lights come down low into the trees and disappear. The scoutmaster's first thought was that a plane had made a crash landing. The boys didn't see the lights, but he told them about them and said he thought he ought to investigate. The boys were afraid to be left alone in the car, and he started to drive on when he peered back into the trees and saw something glowing. This time the boys thought they saw it too. The scoutmaster decided that it was his duty to see if a plane was in trouble.

He had the radio on in his car, and a quarter-hour program was just starting. He told the boys to wait until the program was over, and if he hadn't returned, they were to go to a farmhouse a short way down the road and summon help. Taking a flashlight and a machete, he headed into the woods.

He stumbled through the night, keeping his light on the ground, until he came to a clearing a short distance from the road.

"I suddenly noticed something odd that frightened me," he said. "I felt damp, muggy heat on my face. It did not feel natural. At the same time I smelled a faintly pungent odor.

"I stepped into the clearing and the heat and odor got worse. It felt like radiation from a furnace. I glanced up to check the position of the North Star. It was a clear night and I had spotted the star when I left the auto, to orient myself. The whole sky was black.

"I was paralyzed with fear and turned my flashlight up. The beam shone on the bottom of something. It looked like battleship-gray linoleum. Whatever it was, it was so low I could have jumped up and hit it with a machete.

"I backed up until I could see the stars again. Then I flashed the light up again and could see the object plainly. It was about 50 feet in diameter, with things on the side like ventilators. The device was dome-shaped, with a slightly convex bottom. As I stepped back, the heat diminished and I could feel the cool, fresh air on the back of my neck.

"Suddenly I had the strange feeling that something was watching me. From the saucer there came the sound of something moving, of metal against metal, like a safe door opening.

"A glowing red ball appeared and started to float down toward me. In a reflex action, I threw my arms up to protect my face, with my clenched fists over my eyes. I was engulfed in a red mist and lost consciousness."

Back on the road, the scouts grew frightened, piled out of the car and ran to the farmhouse for help. The farmer called the state police, who relayed the alarm to the sheriff. Two deputies arrived on the scene just as the scoutmaster came stumbling out of the woods.

"He had the most scared look I've ever seen," one of the deputies told me. The scoutmaster poured out his fantastic story to the deputies and then accompanied them back to the clearing. They found his flashlight on the ground, still burning, and a crushed place where someone had been lying.

The whole party went off to the sheriff's office, where the scoutmaster was examined. They found that the backs of both arms were scorched and the top of his cap – long-visored fishing or skiing mode – had been scorched, too. They notified the Air Force.

We questioned the scoutmaster at length the evening after we arrived. He told a consistent story. When we got through, he asked if he could talk to anyone about the event, or should he keep buttoned up? "That's up to you," I told him. "The Air Force doesn't try to censor these stories."

We talked to his employer, who said he was a fine fellow. The next morning we went out to the scene and combed it foot by foot. The only theory we had was that he had been struck by lightning – possibly ball lightning – but there was no sign of lightning having struck the area.

We returned to the base and found it in an uproar. The scoutmaster had a lurid account in the local paper. He reported that "top Air Force officials from Washington" had questioned him. "The Air Force and I know what this thing was," he went on cryptically, "but I'm not allowed to tell because it would create a panic."

I looked at Olssen and he looked at me. "Screwball," we said simultaneously.

The scoutmaster knew that we were from Dayton, not Washington, that we were plain AF captain and a lieutenant, not "top officials," that we had offered no theory about the "saucer," had told him he could talk freely. That afternoon we learned he had hired a press agent. That evening we did some extensive digging into his background, and the next day we flew back to Dayton.

We brought his hat back for a check at the lab. They reported that the scorch marks were peculiar, as if they had been burned by a hot iron. There were folded areas that were not scorched at all. The lab expressed strong doubt that hat was on anyone's head when it was burned.

We sent out a few queries here and there, and found that he had a peculiar background for a scoutmaster. He had told a strange story about serving in the Marines in the Pacific, where he had landed alone on Jap-held islands and mapped them at night to make the Marine landing easier.

We queried the Marines and they told us that he had served six months and never left the country. He had gone AWOL, got mixed up in a stolen car case, had been kicked out of the corps and had served time. We checked the institution where he had done his term and learned that he was a somewhat unstable character, to put it charitably, given to spinning wild yarns. He reportedly had once told New York police he had seen two men hurl a woman out of a skyscraper and that the body landed at his feet. Up sped a black limousine, he said, out jumped two other fellows who picked up the body, threw it in the back seat and roared off. The police went with him to the scene, and sure enough, there wasn't any body there. There wasn't any blood on the sidewalk, either.

We tipped off the Scout council and wrote off the story as a hoax. The fellow kept telling it, however, and it got better all the time. Within a month, the saucer had acquired an unspeakable monster, so foul that there were no words to describe it.

Later we had an even more fascinating "manned saucer" story from a radar station up near the Canadian border. Two radar men stepped out of their shack one night and were astounded to see a great glowing UFO low in the trees a few miles away. The generator that operated the radar set wasn't operating and one of the man ran around to the Quonset hut to get it started.

While he was in the hut, the saucer flew up to the radar shack and halted, hovering in the air. A sliding door opened, and a little man 4 feet high, came walking down some invisible steps. He was quite remarkable, even for a saucer crewman – he had two heads, one an old one and the other a young one. With proper respect for age, the young head let the old one do the talking.

"May I please have a drink of water?" the elderly head asked the radar operator.

The man stammered that they had no water, which subsequent investigation indeed proved to be the truth. The old head thanked him politely, and the creature mounted the invisible steps and re-entered the saucer which flew back to its original position among the trees. A little later the radar pair pointed it out to several people, all of who saw it clearly. The other witnesses, however, insisted that it was merely the moon.

A formal report was filed on this and forwarded to Dayton. We were still puzzling over it when we got a terse supplementary notation from the local intelligence officer who had interrogated the men. Behind the radar shack he had found two cases of empty beer bottles. "Please ignore original report," he wrote. "Disciplinary action has been taken."

In general, we didn't pay much attention to the reports that involved saucer crews, whether they were little men, indescribable monsters, or spacemen with junior and senior heads. Once West Virginia came up with a report of a metallic monster that blew poison gas at some children. We got an urgent phone call from the local newspaper asking us when we would be down to investigate. I took the call.

"Has this monster got a saucer?" I asked the reporter.

"Well, there's talk about some lights seen landing in the vicinity, but no one has located anything."

I asked him how the monster got around, when he walked or flew.

"The stories say he's been crashing through the underbrush," the reporter said, "so I guess he's walking."

"If he walks, he's an Army problem," I said. "Call me back if he starts to fly."

We never got a call, and the monster crashed off into one of the Sunday supplements.

The saucers hit the front pages in 96-point type in July, 1952, when they "buzzed" Washington, D.C. The story caught the Air Force completely off balance and the handling of it got fouled up beyond all recognition. It finally took a couple of generals and a press conference to straighten things out.

It started shortly after nine o'clock Saturday night, July 19, when the Air Route Traffic Control Center of the Washington National Airport noticed some odd targets on their radar scope. They seemed to be the shape and size of aircraft, but they didn't fly right. They would cruise around aimlessly at from 100 to 130 mph and then suddenly vanish – "in a burst of speed," the saucer Boswells added later, in dressing up the story. Shortly before midnight, the National Airport controllers called Bolling Air Force Base, just across the Potomac, and asked if they had anything strange on their radar. Bolling also was picking up strange targets. About this time Andrews AFB chimed in and reported that they had some unknown objects on their scopes, too. Bolling, Washington National and Andrews are all tied together in the common communications net, and they started comparing notes over the squawk box.

Once, at a point close to the Andrews range, where the three radar systems overlapped, they all picked up what seemed to be the same target. Several people at Andrews were alerted and spotted a big orange-red object hovering just about where radar had it.

Washington National called all commercial aircraft in the area and asked them to look for lights that they couldn't identify as other aircraft. At 3:15 a.m., Capital Airlines Flight 807 reported seven lights between Washington and Martinsburg, W. Va. – a section where some of the mysterious blips had shown on the scopes. The captain of the airliner, a man with seventeen years' flying experience, described the lights as hovering awhile and then moving up and down. Shortly later a Capital-National flight approaching Washington from the south reported that a light had followed them to within four miles of the airport.

At 4 a.m. an F-94 all-weather jet fighter was flown into the area and combed it thoroughly and could find nothing.

The location of this flare-up – practically over the White House – plus the radar angle and the fact that a fighter had been scrambled combined to make this story big news. The radar aspects in particular impressed the newspapers and the wire services, and the case was played up as the first time that "saucers" had been spotted by radar. All over the country people said, "They must be real if radar picks them up." The night fighter roaring aloft to chase saucers away from Capitol Hill was the final touch.

Actually, radar is as tricky as the imagination of a scared youngster alone in the house at midnight. There are a number of ways radar can pick up objects that simply aren't there. An inversion layer in the air will bend the radar beam and cause it to interfere with another radar station that ordinarily is out of range. Or inversion will cause the scanning station to pick up ground targets – such as a big truck. On the night the saucers "buzzed Washington" there was a temperature inversion and all the sets were getting weather blips. The fact that three of them showed a blip at the same spot didn't necessarily mean a thing. They all showed blips wherever they were turned.

When we talked to the men at Andrews who had seen the orange-red object they had already figured out that it was a planet. The fact that a fighter had been sent up was not at all unusual. It is standard procedure whenever the Air Defense Command gets a target that they can't identify over a "sensitive" area. That's their job. We couldn't account for the airline sightings, and listed them as unknown.

But by the time we had pieced all this together, the Washington saucer story was a couple of days old, the papers were back on politics and hardly anyone was interested in a complex explanation of just why an exciting story hadn't been true. This time lag was a real drawback in keeping the public informed about the evaluations of the project. Someone out in Seattle or San Antonio or What Cheer, Iowa, would report a saucer and the local paper would call us up and ask, "How about this? What was it, anyway?" We'd tell them, in all honesty, "We don't know. We haven't been able to make our evaluation yet." The story would hit the paper's front page the next day under the headline:

PREACHER SEES SAUCER

AIR FORCE CAN'T EXPLAIN

Just one week after the saucers buzzed Washington, they came back and buzzed it again – and again we stubbed our toe on the story. The reporters got word of the story and hurried to the airport. This time the all-weather fighters were called down right away. Commercial traffic was cleared out of the area and things were set up to work an "intercept." Here the trouble began; some of the procedures used in the situation are classified, so the reporters were shooed out of the radar room. Everyone was excited, and the reporters bewildered by the sudden bum's rush. They knew that "something" had been spotted over the capital again, and pretty soon they heard our jets roaring up and down through the night--while something big went on behind firmly closed doors. The next day the papers broke out with 120-point bold headline type:

SAUCERS ELUDE 600 MPH JETS