Des douzaines de signalements de soucoupes volantes ont resulté de la création d'un observatoire canadien des soucoupes volantes

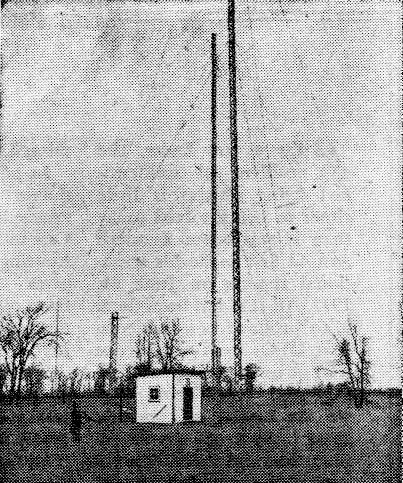

Dans un minuscule bâtiment de seulement 12 pieds2 à Shirley Bay, à 10 miles au nord d'Ottawa, est hébergée l'un des collection d'instruments la plus inhabituelle jamais fourrée dans un si petit espace. C'est le 1er observatoire de soucoupes volantes au monde.

La station d'observation est entrée en opération sans tambours ni trompettes. Au début les représentants du

gouvernement canadien étaient enclins à écarter l'existence-même de la station comme étant le fruit de l'imagination. Le jour avant son ouverture, le Dr. Omond M. Solandt , président du Comité de Recherche sur la Défense, professa une ignorance totale du projet.

, président du Comité de Recherche sur la Défense, professa une ignorance totale du projet. Rien à voir avec le Comité de Recherche de Défense

, dit-il. Cela se révéla assez vrai. La station fut construite par le Conseil de Recherche National et officiellement annoncé par l'hon. Lionel Chevrier, ministre du Transport. M. Chevrier n'a pas expliqué la dénégation du projet par le Dr. Solandt, qui fut prompt à changer sa déclaration, expliquant seulement que son comité n'était pas impliqué dans le projet.

Cependant, nous continuons à étudier les nouveaux signalements

(de soucoupes volantes), a-t-il admit, et

sommes en alerte des possibilités de découvertes de cette nature.

Dans le même temps, des signalements de nouvelles observations de soucoupes sont venues de tout le Canada.

A North Bay (Ontario), le Daily Nugget a un dossier de 16 personnes ayant signalé l'observation de disques de couleur orange. Le journal indique que tous les récits se recoupent de près en termes de taille, couleur, vitesse et comportement en vol.

Un citoyen de North Bay a parlé fin octobre d'une douzaine d'observations nocturnes d'un drôle de globe

orange

vu sortir du ciel du nord-est, errer en avant et arrière à travers l'horizon, puis disparaître.

Fin 1951, 3 personnes signalèrent une observation de jour au-dessus du Lac Nipissing. Chacun la fit depuis une berge différente et n'était pas au courant des autres signalements. Et chacun rapporta avoir vu une étoile ronde et argentée effectuant des manœuvres étranges.

Des disques rouges-orangés sont apparus plusieurs fois au-dessus de la base de jets de la Royal Canadian Air Force de North Bay. Une fois un tel objet a circled, dived and zig-zagged over the field for eight minutes. Another time a disc approached from the southwest, stopped, hovered over the field, reversed direction, and disappeared in a climbing turn.

It is dozens of such reports that have resulted in the creation of Canada's flying saucer observatory - some call it a "dish watching" station. Management of the station is under the Canadian saucer project, called "Project Magnet." Project Magnet was given formal recognition 3 years ago by the Department of Transport on an understanding that it be confined to the broadcast and measurement section of the telecommunications division of the department and that no appropriation of public funds be required for its support. Actually, Project Magnet was created to investigate the possibility of discs powered by magnetic propulsion.

Tremendously complex and expensive equipment has gone into the tiny building at Shirley's Bay. The equipment is designed to detect gamma rays, magnetic fluctuations, radio noises and gravity or mass changes in the atmosphere.

Installed in the little structure is an ionospheric reactor to determine the height, pattern and conduct of the ionized layer of gases several hundred miles in the atmosphere.

There is a new type instrument called a gravometer, imported from Sweden, to measure the earth's gravity; a magnetometer, to record the variations in the earth's magnetic field; a radio set running full volume at 530 kilocycles to pick up any radio noises, and a counter to detect cosmic rays from the outer atmosphere.

Peter Dempson of the Telegraph staff reports that all the instruments are connected with a control panel filled with lights, dials and other instruments which record the individual findings on paper.

The station is not manned, but is connected directly by an alarm bell system with the nearby ionosphere station at Shirley's Bay where a staff of telecommunications experts are on a 24 hour duty.

Eventually, relays will carry the information recorded by the instruments in the sighting station to the main building. Any unusual variation in the information they provide will trigger the ionosphere recorder - an instrument which transmits a radio signal 250 miles into the sky. The signal bounces off the heavy layers in the ionosphere and is reflected back to be picked up by a radar-like instrument. Officials believe that it would record any flying saucer in the area. "If anything should happen, the findings of this recorder prove very valuable," one official said.

The effective range of the other instruments is limited to about 50 miles. Wilbert B. Smith, engineer in charge of the project, believes on the basis of past reports there is a 90 to 95 % probability that the sighted phenomena which the station is set up to observe actually do exist. La position officielle de M. Smith est ingénieur en charge de la division des télécommunications du Département des Transports Canadien. Lui et les membres de son équipe ont mené des enquêtes sur les soucoupes pendant 5 ans as a hobby and Project Magnet now represents the Canadian Government's official seal of approval on their efforts. Smith himself believes that there is a 60 percent probability that flying saucers are "alien vehicles."

Top Canadian scientists, including Dr. C. J. MacKenzie, former head of the National Research Council and the Canadian Atomic Energy Project, have consistently refused to ridicule saucer reports.

"My own opinion is that the reports are valid

," Smith dit à Gerald Waring, Canadian news writer. "The optical illusion explanation is lovely, but in every sighting there is always some factor which rules it out. So we've decided to learn just what flying saucers are."

Because of the comparatively large number of saucer sightings in Canada, and despite the fact that most of his instruments have only a 50 mile range, Smith predicts that his instruments will report at least one saucer within a year.

He points out a fact that may or may not be significant – that saucer sightings increase when planet Mars is nearest the Earth. These close approaches occur every 26 months. Next summer Mars will come within 40 million miles of Earth, and in 1956 it will come within 35 million miles.

Others aiding engineer Smith include Dr. James Watt, theoretical physicist with the Research Board; John H. Thompson, technical information expert on telecommunications; Prof. J. T. Wilson of the University of Toronto, and Dr. G. D. Garland, gravity specialist with the Dominion Observatory.

The Shirley's Bay observatory had its first major test in January, just two months after it was established. A ball of fire flashed across Ontario, Quebec, and New York state in the early dawn and may have fallen into Georgian Bay. Startled residents of Ontario and Quebec called police and radio stations for an explanation. From Parry Sound came reports of an explosion "like a bomb

."

The observatory was able to report that it was a meteor. Director Smith said that the object was noted at the flying saucer station but failed to register on the delicate instruments, indicating that it definitely was not a saucer.

"Not a squiggle on our electronic devices," Smith said. "If it had been a saucer, our recorder would have shown it." Smith pointed out that his station's electronic devices would not detect meteors unless they were of "great mass" and passed very close.

This leaves no doubt whatever that the little building on Shirley's Bay is a flying saucer station only.