Instrumented meteor astronomy is a comparatively young field dating back not much before 1936 when the Harvard Meteor Project began. Determination of mass distributions, size and composition has been difficult because results have to be arrived at by inference only instead of from studies of samples collected in the field.

Current theory holds that meteors originate from two sources: comets and asteroids. It is thought that meteors which survive long enough in our atmosphere to reach the surface are asteroidal in origin. From spectroscopic evidence it appears as if comets were composed of solid particles - "dust" - weakly bound by material which can exist in solid form only at very low temperatures. Only the dust can exist for an appreciable time in the solar system, and it is these solids which appear as cometary meteoroids. As a matter of interest, this does not preclude the deep penetration of our atmosphere by large cometary fragments. The Tunguska Meteor of 1908 is thought to have been such a fragment, and the devastating effect of this encounter is still visible today (Krinov, 1963).

Almost all meteorites in museum collections were found accidentally and the time of landing for about half of them is unknown. Seeking to increase the recovery rate and to pinpoint the time of arrival, the Smithsonian Institution began to design the Prairie Network in the early 1960s (McCrosky, 1965) in such a way as to increase the area coverage over that of the Harvard Project and to improve the probability of observing large, bright objects. Between 1936 and 1963 four technical advances proved particularly important in the basic design of the system: the Super-Schmidt camera, much faster photographic emulsions, radar, and the image orthicon. The Super-Schmidt and high-speed film were originally used in an effort to determine the trajectories of faint meteors having initial masses of ~102 gm. The radar and image orthicon have been combined into a system for the study of meteors which are fainter than the Super-Schmidts were capable of detecting, and which are presumed to be of cometary origin. A grant from NASA established the network and the first prototype photographic station went into operation at Havana, Ill. in March 1963. About a year later, the network first functioned when ten stations began working reliably.

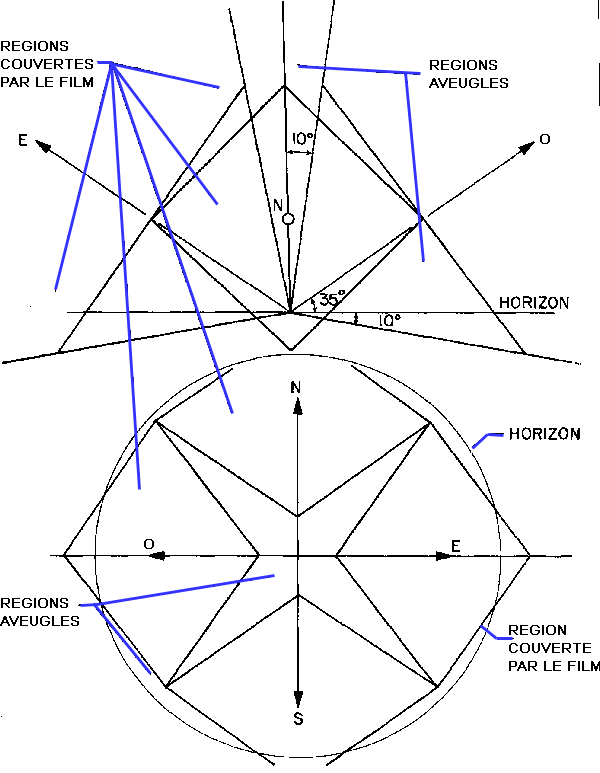

The complete network now consists of 16 stations of four cameras each, located at the apices of a set of nesting equilateral triangles having a separation of 225 km. Each of the four cameras is aligned with a cardinal point of the compass with the diagonal of its 9.5 sq. in. film oriented vertically. The optical axis of the camera is elevated at an angle of 35° to the horizon, but as the effective field of the present lenses is ~100° one corner of the film will photograph ~1O° below the horizon and the extreme of the opposite corner falls short of covering the zenith by ~10° (See Fig. 1) As a result, there are five blind spots, one vertical and the other four at true compass bearings of 45° 135°, 225° and 315°, amounting to about 20% of the total hemisphere. All 16 interlocking stations cover a total impact area of 1,500,000 km2.

The Super-Schmidts are capable of recording stars with a photographic magnitude of as low as Mpg = +3, but the network cameras have considerably lower sensitivity, computed at Mpg = -3.

The angular velocity of the meteorite is determined by interrupting the streak of its path on the film by means of a shutter that runs continuously. The shutter motion is interrupted at regular intervals in order to produce a timing code that indicates time in reference to a clock face photographed on each frame. This permits fixing the time of passage with respect to the exposure interval.

The standard exposure is three hours so that three to four frames are produced each night. Operation of the camera is controlled by photosensitive switches that turn the system on at twilight and off at dawn. To prevent fogging by moonlight or other bright sky conditions, each camera is equipped with both a neutral density filter and a diaphragm activated by a photometer.

Other features insure the proper exposure and recording of time intervals of meteors having a photographic magnitude greater than Mpg = -6.

Stellar magnitudes are stated on a logarithmic scale. A difference of five magnitudes corresponds to a ratio of brightness of 100. Because the astronomers traditionally have referred to a bright star as being of "the first magnitude," and less bright stars as being "second magnitude" or "third magnitude" stars, the sign given to a magnitude is inverse to its brightness. An object of MV -1 is, by this convention, 100 times brighter than an object of MV +4 (a difference of five magnitudes). Magnitudes of some familiar heavenly bodies are: sun -26.72; full moon ~-12; Venus -3.2 to -4.3; Vega +0.1; Polaris +2.1. The faintest magnitude visible to the normal, unaided human eye is about +6.

Photographic (Mpg) and radar (Mrad) magnitudes are related to visual magnitudes by coefficients which are functions of the wavelength of the radiation as well as the characteristics of the detector.

Although a meteor may be recorded by more than two cameras or stations, only two views are necessary to determine altitude, velocity, and azimuth. The two best views are those in which the line joining them is the most nearly perpendicular to the trajectory. Such stereo pairs will detect meteors at altitudes of 40-120 km. If the measurements indicate that the meteor may land in a region relatively accessible to network personnel, a third view of the trajectory, downstream from the first pair, and where the meteor has fallen to an altitude of between 10 and 40 km., is then measured to determine the rate of momentum loss from which the impact ellipse is computed.

Exposed film from one-half of the stations is collected every two weeks and scanned at field headquarters in Lincoln., Neb. The rate of acquisition of film is ~500 multi-station and ~500 single-station meteors per year. Frames with meteors from one station are cut out of the film strip and a search is made for views of the same event taken at other stations. The assembled events are then sent to Cambridge, Mass. for measurement. It is necessary to measure the length of every interval on the meteor track produced by the shutter, the positions of about forty stars, and to make densitometric measurements of the trace.

One of the most important functions of the network is to facilitate recovery of meteoritic material. The network's design is adequate to provide an "impact error" of 100 meters for the "best determined objects." But such accuracy fails to guarantee recovery because the object of search is nearly indistinguishable from the more common field stones. One recent search occupying 150 man-days resulted in no recovery. Since the start of the project some 500 man-days of search have yielded no recoveries.

In contrast, the Canadian "network," which was not yet in operation by June 1968, has already recovered at least one meteor by careful and extensive interrogations of persons who had witnessed meteor falls. Similarly, in Czechoslovakia, four pieces, out of the many which make up the Pribram meteor, were recovered before the impact point had been determined from data obtained by a simple two-station system not designed for this purpose.