La milieu des années 1950s produisit aussi une tentative de trouver des

r�gularit�s statistiques ou un "motif" dans les

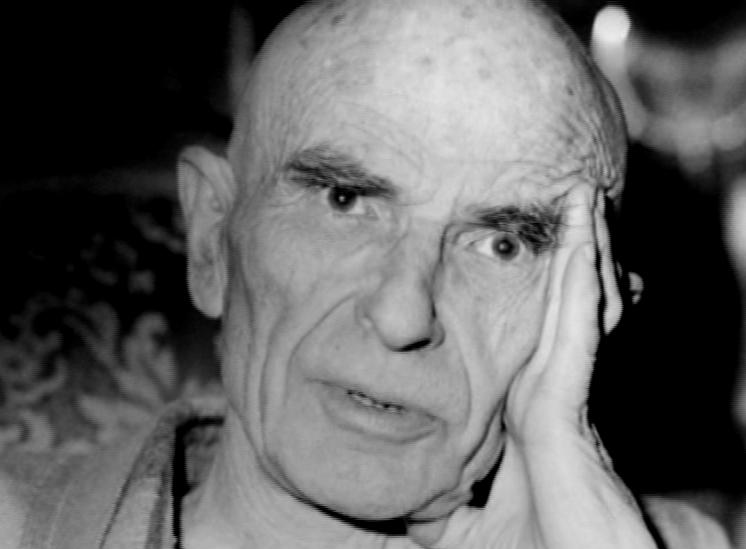

observations d'ovnis. Aime Michel (1958), un journaliste français qui a étudi� et �crit

sur les ovnis, pensait avoir trouvé une tendance statistique prononc�e pour les lieux où les ovnis sont

signalés en un intervalle de temps court comme 24 heures à reposer sur une ligne droite, ou plus exactement, sur

un grand cercle sur la surface de la terre.

(1958), un journaliste français qui a étudi� et �crit

sur les ovnis, pensait avoir trouvé une tendance statistique prononc�e pour les lieux où les ovnis sont

signalés en un intervalle de temps court comme 24 heures à reposer sur une ligne droite, ou plus exactement, sur

un grand cercle sur la surface de la terre.

Pour d�crire cette tendance supposée il inventa le mot "orthot�nie" en 1954, deriving it from the Greek adjective "orthoteneis," which means stretched in a straight line.

He first noticed what seemed to him a tendency for the locations to lie on a straight line with regard to five sightings reported in Europe on 15 October 1954. These lay on a line 700 mi. long stretching from Southend, England to Po di Gnocca, Italy.

Another early orthotenic line which has been much discussed in the UFO literature is the BAYVIC line which stretches from Bayonne to Vichy in France. Six UFO sightings were reported on 24 September 1944 in the location of the ends and along the line.

When Michel first started to look for patterns he plotted on his maps only those reports which he had described as "good" in the sense of being clearly reported. Later he decided to plot all reports, including the "poor" ones, and found the straight line patterns in some instances.

A peculiarity of the supposed orthotenous relation is that the appearance of the UFOs in these various reports along a line may look quite different, that is, there is no implication that the sequence represents a series of sightings of the same object. Moreover the times of seeing the UFOs do not occur in the order of displacement along the line, as they would if the same object were seen at different places along a simple trajectory.

Continuing his work he found other cases of straight line arrangements for UFO reports in France during various days in 1954. At this time there were an unusually large number of such reports, or a French "flap." But not all reports fell on straight lines. To these which clearly did not he gave the name "Vergilian saucers" because of a verse in Vergil's Aeneid, describing a scene of confusion after a great storm at sea: "A few were seen swimming here and there in the vast abyss."

Without understanding why the locations of UFO reports should lie on straight lines, this result, if statistically significant, would indicate some kind of mutual relationship of the places where UFOs are seen. From this it could be argued that the UFOs are not independent, and therefore there is some kind of pattern to their "maneuvers."

The question of statistical significance of such lines comes down to this: Could such straight line arrangements occur purely by chance in about the same number of instances as actually observed? In considering this question it must be remembered that the location of a report is not a mathematical point, because the location is never known with great precision. Moreover the reports usually tell the location of the observer, rather than that of the UFO. The direction and distance of the UFO from the observer is always quite uncertain, even the amount of the uncertainty being quite uncertain. Thus two "points" do not determine a line, but a corridor of finite width, within which the other locations must lie in order to count as being aligned.. The mathematical problem is to calculate the chance of finding various numbers of 3-point, 4-point ... alignments if a specified number of points are thrown down at random on a map.

Michel's orthoteny principle was criticized along these lines by Menzel (1964), in a paper entitled, "Do Flying

Saucers Move in Straight Lines?" This triggered off a spirited controversy which included a number of papers in the

Flying Saucer Review,

for 1964 and 1965 by various authors.

The most complete analysis of the question to be published to date is that by Vallee and Vallee (1966). They summarize their work in these words:

The results we have just presented will probably be considered by some to be a total refutation of the theory of alignments. We shall not be so categorical, because our data have not yet been independently checked by other groups of scientists, and because we have been drastically limited in the amount of computer time that we could devote to this project outside official support. Besides no general conclusion as to the non-existence of certain alignments can be drawn from the present work. The analyses carried out merely establish that, among the proposed alignments, the great majority, if not all, must be attributed to pure chance.

The point is that while the straight-line theory, as far as we can say, is not the key to the mystery, a body of knowledge has been accumulated and a large edifice of techniques has been built, and this development reaches far beyond the negative conclusion on the straight-line hypothesis.

As matters now stand, we must regard as not valid the work on orthoteny and "the straight-line mystery."